Abstract

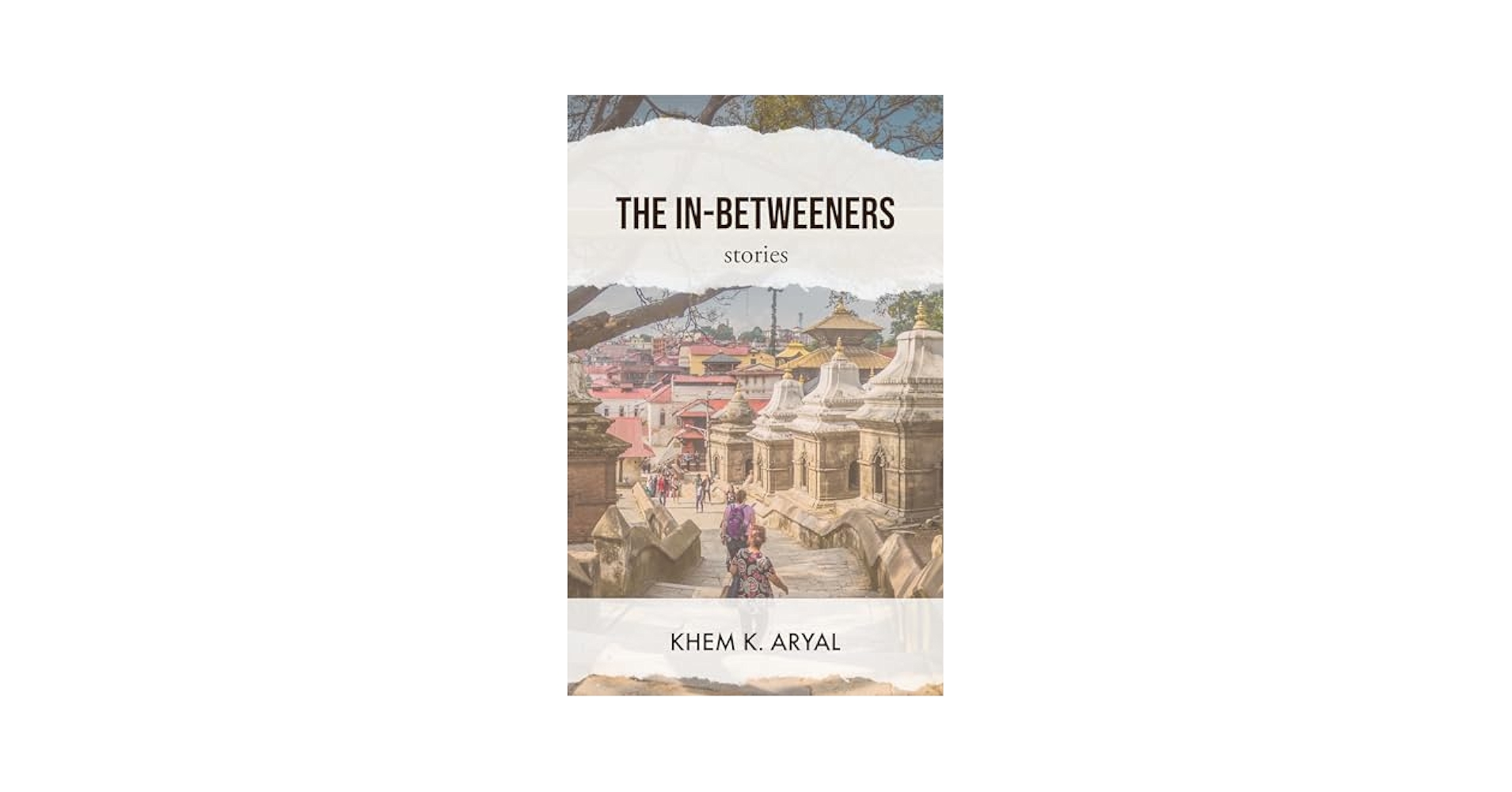

This review essay presents a critical reading of The In-Betweeners (2023), an arresting collection of stories by Nepali American author Khem K. Aryal. By drawing on Benkirane and Doucerain’s model of intersectionality, it covers the characters’ enmeshed and superimposed diasporic identities and emerging subjectivities, and contributes to critical study of different dimensions in Nepali diasporas in America, Nepali diasporic literature, and Nepal as a close and distant homeland.

Keywords: The In-Betweeners; Nepal and Nepali American diasporas; diasporic identities and subjectivities; Nepali diasporic literature; intersectional rhetorics

Amid certainties and uncertainties, life is a conundrum—and a difficult choice, no matter where. It is more helpful, though, when hinged on future possibilities—on newer subjectivities or alterities in the making that bring us light and joy. This is more so while away from home—whether in flights of sweet choices or last options.

This view of mine has been reaffirmed after I read Nepali American author Khem K. Aryal’s The In-Betweeners (2023) — a collection of thirteen gripping stories of Nepali diasporic lives in America. Aryal, via different characters, strongly reminds of Hindu mythology’s Trishanku, who in his self-chosen journey to heaven made possible by his guru Vishwamitra, gets hurled away by gods and is stopped in midair—upside down—by the sage—until the sage creates a parallel heaven for him. This heaven is where Trishanku is thought to have ruled as its king, however in his upside down posture, accepting the word given to gods by Vishwamitra—the word to maintain piety toward natural law and livity—soon after the creation of this heaven in utter rage against gods’ show of power. Similar strandedness is what most of the characters in this collection live, strained and/ or resilient.

Here you meet university teachers, students, visitors, refugees, DV winners, illegal immigrants, hypocrite asylees, and war criminals, among others. Interestingly, this book marks a shift both in nature and presentation of stories of Nepali diasporas. While the earlier Nepali diasporic stories set in the 19th and 20th centuries primarily sing of, including homelessness, heartrending cruelty, physical abuse, terrorizing threats, debt slavery, discrimination, and (labor) exploitation in Nepal’s neighboring countries, as evinced by Govinda Raj Bhattrai’s masterpiece Muglan (2012; 1975) set in Bhutan, this collection takes the reader to a whole new world and shows polychromatic realities of Nepali diasporas there, with each story starting in the American soil and frequently transporting the reader to Nepal.

Another beauty of this book—or rather of the author’s craft—is the presentation of the ordinary as substantially engrossing. Yet these stories give only marginal space to the Westerners. But this is understandable, given the focus of the book. For the very same reasons—if not for others, this book is different also from collections of diasporic stories authored by other Nepali American authors like Samrat Upadhyay and Manjushree Thapa.

As a tapestry of interculturally intriguing and/or psychologically disturbing stories written in very lucid language, the collection celebrates diasporic hearts and minds that range from bewildered to joyous to broken to obsessive ones. Personally, I found the book interesting from the perspective of intersectional rhetoric—“a rhetoric that places multiple rhetorical forms on relatively equal footing” (Enck-Wanzer 2006, p. 177).

Originally envisioned by Crenshaw (1989; 1991), the concept of intersectionality highlighted the enmeshed or superimposed interconnectedness of social categorizations such as age, gender, ethnicity, language, social class, and legal status. Of late, intersectionality/ a model of intersectionality has also been proposed to study multidimensional and complex (marginalized) identities in diasporic settings (Benkirane & Doucerain 2022, pp. 152-153), and this I draw on, in this review essay, to critically read, in particular, three subjectivities or alterities in the making as to how these characters view their life in America and Nepal. These in-betweeners can be identified as pro-American, pro-Nepali, and others in between these two.

At a time when the exponentially increasing ‘exodus’ or ‘foreign settlement’ is being constantly contested as but escapist culture in political or politically motivated educational agendas in Nepal, Aryal in this collection dissects this rhetoric as but hollow, forwarding a subtle but critical meta-discourse: Who would have deserted the country in the first place, given that the systems back home were just and fair—or supportive of quality education—or conducive to a living well-deserved—or simply ensurers of peace, stability, clarity, and optimism? Like in several other stories of this collection, Shyam Prasad and others in “Laxman Sir in America,” for example, strongly maintain this view.

Indeed, for those characters who temporarily or permanently close the topic of returning home, Nepal, though dearest motherland, resembles a chaotic mythological space. They occasionally reflect back on the native spaces and sardonically or otherwise enumerate: trickeries, manipulations, exploitations, loud rhetorics, nepotism and discrimination, poltiks (a contemptuous expression for filthy politics) and institutional degeneration, intransparency, corruption, impunity, blame-games, conflicts, and superstitions prevail almost everywhere in Nepal, and so do unemployment, poverty, frustration, restlessness, pessimism, and cynicism. This is, unfortunately, so very close to the Western/ Occidental projection of the East in the 19th and 20th centuries. But these attributes are, broadly speaking, the glaring realities that most Nepalis have been living for decades—with new kings for the old one, with maddening transitions that never end, with hurdles in every nook and corner, with traps and abuses, with whimpers and uproars. Unfortunately, this is still the case even after the decade long civil war of the 90s. The very scenario back home, for example, nudges the narrator in “Laxman Sir in America” to assert that people, particularly from lower middle class, have “neither a present nor a future in Nepal” (p. 4). This picture of Nepal shoves the reader to the extent of thinking that perhaps many citizens in Nepal are already feeling like they are in diasporas within the country itself. Contrary to this, their projections of American spaces appear like ‘balm on the wounds’. For example, Shyam Prasad in “Laxman Sir in America” dismissively exclaims that America is “everything” (p. 12) and Santosh in “Mrs. Sharma’s Halloween” tells his mother that he and his family will not survive “in that country [Nepal]” (p. 70). So what is ‘good’ in America? For this text-inspired question’s sake, let us go past the “Sword of Damocles” (Rubin 2025) currently hanging from Trump’s administration in America, for the book itself was published before Trump’s erratic and autocratic rule and celebrates stories woven in and through peaceful multicultural American society.

Each of these stories adds a new façade, and these characters, whether acculturated or not, have their own take on this. For many, America appears great, no matter what, for it affords them a range of these attractions: systematic life, fine environment, world class education, abundance of employment, encouraging prospects in entrepreneurial spaces, social security, clarity, optimism, better life, autonomous independence, and joyous living, among others. In this environment, they sooner or later hope to buy a house or obtain Green Card and American Citizenship, the last of which appears as a joyous culmination of their years of tiring wait and struggle in America. For students, academic life in America appears enticing and therefore much coveted, as in the case of Gorakh in “The Lucky Plant.” Interestingly, Gorakh, who has already spent around three years as a student in America, and now a PhD student, resorts to politely indirect and even symbolic ways of communication—indeed, a typical Nepali style, which goes against Americans’ preference for direct and clear communication. This he does to get in his department head’s good books—via the means of winning in an auction a jewel orchid donated by his department head. Yet he does not appear a sycophant from any corner. Similarly, ‘acculturation’ is not at all problematic for younger generation and parents are secretly happy about it, as in the case of Vishworaj in “American Son.” Vishworaj, while worried at the fact that his son is being completely Americanized, cherishes the thought that it is good for his son in the long run. Nonetheless, a collective consciousness about their native identity or Nepali language and culture also runs in their blood, as is evident in “Lost Country” in which the reader is amused to learn about “the Nepali school” where the volunteering teachers are not allowed to speak English, fearing that the kids may not learn Nepali well or sooner. On the other hand, some characters use America as a safe hideout. For example, in “Thapaliya-ji the Social Worker,” an ex-minister in Nepal now mopping floors in the US slyly noses around and takes his Muslim boss in confidence and starts a business venture of his own, apparently by channeling his black money hoarded back home. And this is interesting for the fact that this ‘cunning player’ in America is not yet done away with his ‘old ways’ back home.

Clearly, most of these characters appear trading off one or the other opportunity or positive aspect in America, including their better income in American dollars (compared with meager or no income in Nepal), against the heavily taxed American socioeconomic system, which they think is very much biased against the working class people they belong to. This way, they remind the reader of Bhabha’s idea of the space of negotiation (pp. 38, 183). But still the horizon is wide, open, and embracing.

Referring back to Kant and Sartre, Davis (2006, pp. 336-337) reminds that all individual subjects, no matter where they are, have something diasporic about them; and therefore, they are looking to something desirable yet to be created—while busy with creating something. This is more applicable to the characters who temporarily or permanently close the topic of returning home.

However, a majority of the characters sound like they are in age-long ‘in transit’—full of agitation and drama, oscillating all the while in “neither here nor there” (Turner 1974, p. 232) states of minds, or expressing (extreme) dissatisfaction with their American life. And this builds the most important subtext in the book. These characters, though they appear fighting back this or that barrier to normalize their lives, cannot pass through to “a deepening sense of connectedness to the Other” (Hazell 2009, p. 62) from their eluding alterities (Overgaard & Henriksen 2019, p. 381) or alterities of distaste for their diasporic existence, and this eventually leads one or two of them to even permanently return to Nepal, no matter what. Behind this, there are several reasons, both external and internal.

The book is full of grudges that life in America offers no dignity but servile/ menial jobs, and is too lonely, mechanical, complex, cold, and humiliating. Though most of these characters tend to cherish the fact that they are earning in American dollars and living a life that is far too great, they time and again become homesick, mostly when exhausted from their ‘machinized’ life, missing the kind of close and warm intimacy they enjoyed back home. Their contact with the locals is mostly limited to casual workplace conversations, which, though it functions as ‘little windows’ into American life and politics, does not help them much, as in the case of Laxman Sir in “Laxman Sir in America.” Laxman sir, a DV lottery winner, sounds like he is now ‘debilitated’ with his menial job at Amazon Fulfillment Center, when he boastfully reveals how greatly he enjoyed doing local politics in Nepal—often turning it to his advantage—while working as a soon-to-be a retired school teacher. It is quite amusing when this character has very hard and insulting time at work because of his poor English and the resulting misunderstandings. He feels declassed and not respected the way he was respected back home, so humiliation runs a long race in his heart, often transporting him to the easy-go-lucky life back home that afforded to him sweet gossips with friends over tea or coffee, political connections, and, above all, a life of respect. So, when heated by pro-American Nepali diasporic people, he strongly counter-argues that America is “not everything” (p. 12), and is ready to return home; but, to his wife, this whim of his is nothing but sheer stupidity. Interestingly, a majority of female characters, who still appear practicing their native cultural values and deferring to patriarchal norms, exhibit more tolerance in the face of disillusionments, in their interactions with their male counterparts, and in their wait through protracted processes for the Green Card and/ or American Citizenship.

However, a few of these characters are not just homesick but pathologically obsessive to return to Nepal, missing something close to their heart and soul. This something ranges from—of course away from their mechanical existence—inclination toward a languid life in the countryside or easy life back home to sweet old days’ memories to love for the dear motherland and its exotic beauty and warm culture. For instance, Dharmaraj in “The Return,” another DV winner now almost well-established in America with his family, goes to the extent of faking a heated quarrel with his wife and sons—by physically abusing his wife; and this he does just to plot a strong reason to return to Nepal for good. This of course invites the police, after which the situation further worsens: He goes through self-torturing emotions and self-talks and causes torture to others. Unable to see the psychological damage caused this way, either to himself or his family members, he remains trapped in the “internal rhetorics” (Nienkamp 2001, p. 3) of his own that, as time passes, intensifies as more haunting. This takes him to speak from his hidden alterity, complaining that his wife and sons unfortunately could not see his love beneath what he did for them by bringing them to America and giving them everything he earned there. His pathological obsession to return home, and that too after fourteen years of his acculturation in American life, starkly brings to the fore his close reading of his being a puppet in the traps of American neoliberal (market) spaces: “The second you land here, you become its slave” (p. 176). Work, work, and work, and pay taxes and instalments of insurances—all your life—and try to be happy in this gloomy trap, his tone impinges—both on the narrator and the reader.

However, such critical tone is generally not found in the words of those who enjoy much higher social status in American life, as in the case of the major character in “Lost Country.” This particular character in this story, at least with his academic milieus and associated spaces, resembles the author himself as a university teacher in the US, and is interestingly addressed as ‘you’—perhaps a second person projection of the writer’s own self or experiences in the US.

While, among others, ‘work’ in America appears to be creating exasperating tunnels for these characters—which in itself is very ironic given the fact that many are duped or dying to get employment here in Nepal, ‘lack of time’ is another descriptor of suffocation for many. In a society where “time is money” (Althen 2005, p. 10), most of the characters seem to be dying for time. For instance, the couples in “Rescued” and Jagan in “Overstayed” bitterly regret that they do not have enough time for self and/ or family. Jagan, an artist from Nepal—now working illegally as a cook in America, has overstayed—not only from legal point of view but psychologically—a state of disillusionment that he reaches after multiple failed efforts of obtaining ‘Green Card’—and a state of crazy restlessness to be home. Similarly, Manita in “Visa for Mama”—the most disturbing story in the collection—pines for the bygone times: The times that she spent (most probably in Nepal) with her mother who is no more now. ‘Time’ here changes into so many things, flowing everywhere: A dark tunnel left behind by the death of her mother, the border between the world and beyond, the geographical distance that she could not just leap over and be with her mother in her final days, the trauma and suicidal tendency that she is grappling with, the demand to be normal with her loving husband in this space—or when she goes to the extent of applying for a visa for her dead mother. Often, she is neither in America nor in Nepal—when she is trapped within herself, within her delusional alterities. At other times, she appears trying to be normal. In her case, diaspora looks like a curse in blessing—like it was in the case of the upside down Trishanku. Heaven, but no heaven. Blurring of time and space and faking normalcy also goes parallel in “Mrs. Sharma’s Halloween.” While Mrs. Sharma, a visitor to her son’s place, reflects that even the great Nepali festivals – Dashain and Tihar – feel like “mourning” (p. 63) in America, which her son and daughter-in-law concede to, she later goes to the extent of amusing the reader when, finally, after fearful amazements, she takes Halloween for Gai-jatra and feverishly feigns celebrating it—a cocktail of a sort—with her grandkids. But fraudulent ways of some characters—other forms of faking—ultimately give up in several cases, particularly when these characters’ fixes and schemes fail or their psychological barriers explode. At such exhausted moments, they intensely undergo homelessness and miss Nepal more—and few of them, as in the case of Jagan in “Overstayed,” are all set to open the door to their native country that they once closed for good. Interestingly, in the words of (ultra-)nationalistic Nepalis, they do not remain but remain ‘opportunistic’. Perhaps, and perhaps not. Had their plans worked as expected, would they even think of returning? But yes, a few of them also realize that America is not the ultimate happiness they now understand they are after, as in the final realization of Jagan, who now wants to return home and resume his artistic dreams or do something that gives him joy.

Now to some absences I felt while reading these stories. Except for khir and sel-roti, I missed gundruk, sinki and sidra (typical Nepali food items). Yet some in-betweeners themselves metaphorically stood for them, as seen in this essay. Bansuri (flute) also appeared only as a dream, as glimpsed by the visiting mother in “Mrs. Sharma’s Halloween.” In these highly liberal spaces, or the parallel heaven, I also missed the kind of alien misgivings I had when I was told about some four or five shootings across Chicago the very night I stayed at a hotel in this city in May 2023, just when I was checking out for the conference at the University of Illinois, in which I was going to participate as a presenter from Nepal. Here I also missed the state-paid, shabby, and drunk beggars of Chicago, who begged for money and/ or shouted at pedestrians, including myself. Later, during my stay in the US, I was told that these beggars become ‘kings’ for fifteen days—of course metaphorically—and only for the rest of the month, they go homeless. Homeless? A diaspora within one’s native country—and in America at that? This did make me stop and think. Together, grimacing at another darker truth about which I heard in Kentucky—that of some Nepali girls going for quick and easy money, mostly in Texas, Las Vegas, California, Colorado, and New York, which of course is part of the dehumanizing neoliberal market—could have helped make the collection even more representative. But then, this, too, is covered, however only implicitly, via Sumitrey’s character in “How Not To Come To America.” This story reminded me of fairies, say Menaka and Urbashi, in lord Indra’s heaven. Though fairies in the heaven, they are slaves to the enthralling grandeurs of the heaven.

Indeed, the parallel heaven is not just another place; it is everywhere—here in Nepal, there in America, or elsewhere—anywhere; it is the very train of subjectivities, alterities and (rebellious) choices one lives, no matter where. And stories of the parallel heaven, as seen so far, are often provoked by the lived struggles or are inspired by personal dreams, and they shed much light not only on the making of diasporas but also of human conditions in general—whether inside a country or away from it. These stories stand a witness to this, individually and collectively.

Whether in for-, against-, or in-between positions, most characters in this collection appear to resemble Trishanku in one way or another. Despite this, Nepali diasporas in America clearly appear both debating and celebrating their lives (Werbner 2006, p. 896) and are in both bounded (homeland-centered) and unbounded (fluid/ non-essentialized) states— than in radically dynamic processes (Mavroudi 2007, pp. 467-474). Understandably, the major reason behind this is these stories basically deal with the first generation diasporic Nepalis in America, and therefore, their dynamically radical metamorphoses are yet to come—more in their upcoming generations, as hinted in the book. In essence, The In-Betweeners is more than a collection of polychromatic realities of Nepali diasporic spaces in America, for it frequently ushers the reader to Nepal—to Nepal as it is, via discursive routes.

References

Althen, G. (2005). American values and assumptions. In P. S. Gardner (Ed.), New directions: Reading, writing, and critical thinking (pp. 5-13). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Aryal, K. K. (2023). The in-betweeners. Braddock, PA: Braddock Avenue Books.

Benkirane, S., & Doucerain, M. M. (2022). Considering intersectionality in acculturation: Bringing theory to practice. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 91, pp. 150-157.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.10.002

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Bhattarai, G. R. (2012). Muglan (L. S. Pathak, Trans.). Kathmandu: Oriental Publication. (Original work published 1975).

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), pp. 1241-1299.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(1), pp. 139-167.

Davis, C. (2006). Diasporic subjectivities. French Cultural Studies, 17(3), pp. 335-348.

Enck-Wanzer, D. (2006). Trashing the system: Social movement, intersectional rhetoric, and collective agency in The Young Lords Organization’s Garbage Offensive. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 92(2), pp. 174-201.

Hazell, C. (2009). Alterity: The experience of the other. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse.

Mavroudi, E. (2007). Diaspora as process: (De)Constructing boundaries. Geography Compass, 1(3), pp. 467-479.

Nienkamp, J. (2001). Internal rhetorics: Toward a history and theory of self-persuasion. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Overgaard, S., & Henriksen, M. G. (2019). Alterity. In G. Stanghellini, M. Broome, A. V. Fernandez, P. Fusar-Poli, A. Raballo, & R. Rosfort (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of phenomenological psychopathology (pp. 381-388). Oxford, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Rubin, G. (2025, January 22). Donald Trump erratically waves sword of Damocles. Reuters.

https://www.reuters.com/breakingviews/donald-trump-erratically-waves-sword-damocles-2025-01-21/

Turner, V. (1974). Dramas, fields, and metaphors: Symbolic action in human society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Werbner, P. (2006). Theorising complex diasporas: Purity and hybridity in the South Asian public sphere in Britain. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(5), pp. 895-911.

This review essay was presented at the conference “Indigenous Environmental Knowledge and Nomadic Wisdom: Discoursing in the Disciplines of Archeology, Anthropology, and Post-colonialism” organized by SAFAR South Asia, Kathmandu, Nepal, in 2024.

Follow Us